From here on out I will discuss translations per decade. I have recently decided to do this, so, unfortunately, in my previous post, I have already discussed two publications issued in 1840. Ichabod Charles Wright’s Paradiso and John Abraham Heraud’s unpublished manuscript of the Inferno. You can read about them here. This post will skip those. Moreover, I will only discuss complete translations. A future post will go over partial translations of at least one canto. There are about a dozen in the first half of the 19th century.

This decade saw five complete translations, though two were unpublished and one of those is lost. Besides the two discussed in the previous post, there was John Dayman’s Inferno in 1843, Thomas Wade’s unpublished, and now lost, Inferno in 1845-46, and John Aitken Carlyle’s Inferno of 1849.

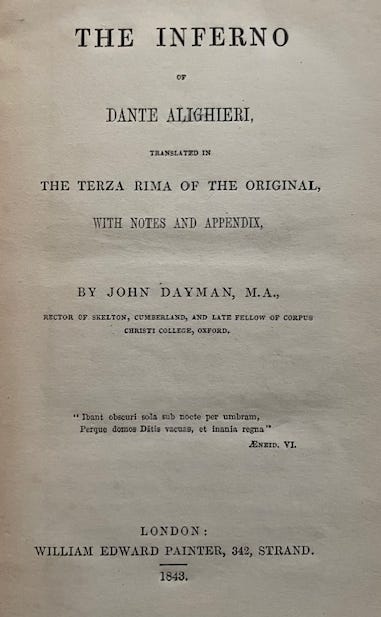

1843 - John Dayman - Inferno

In 1843 John Dayman published the Inferno of Dante Alighieri.1 His translation is in terza rima and it is the first translation of a complete cantica in that form. Later, in 1865, Dayman published the Divine Comedy in terza rima, but by then there were already other translations in terza rima.

In the brief preface regarding his choice to use terza rima, Dayman says he is “subservient to the principal object of the Poet.” He expands on this in the preface of his Divine Comedy, published in 1865, because he states his use of terza rima was accused of being a “deleterious ingredient”2 He pushes back stating, not only were “the great masters … sedulously observant of metre as an instrument of expression," but the form of a work of art is essential to the art itself and is “a significant exterior … which gives a true evidence of its hidden essence.”3

1845-1846 - Thomas Wade - Inferno - Unpublished and Lost.

This section on Thomas Wade was taken and tweaked from my earlier post A Lost Inferno - 1804. It recounts the search for the manuscript of Thomas Wade’s Inferno which ultimately ended in the discovery of Robert Watson Wade’s Inferno.4

My search began with Paget Toynbee. In his Dante in English Literature, published in 1909. He states the Wade manuscript was owned by H. Buxton Forman who printed an excerpt from the Inferno (Canto 34, lines 127-139) in Literary Anecdotes of the Nineteenth Century in 1895.5 Here is the 1909 entry":

“In 1845-6 he made a translation of the Inferno in the metre of the original, of which a specimen (Inf. xxxiv. 127-39) was printed by H. Buxton Forman (the owner of the MS.) in Literary Anecdotes of the Nineteenth Century (vol. i. p. 65).”6

Toynbee mentions Wade again 12 years later, in his Britain’s Tribute to Dante, published in 1921. This time his entry states the manuscript is in the Macauley Collection at the University of Pennsylvania and an excerpt was published in the New Quarterly Review in April of 1877. The previous excerpt from the Literary Anecdotes of the Nineteenth Century was not listed. Here is the 1921 entry:

“Thomas Wade : translation (terza rima) of the Inferno.

[Unpublished ; the MS. formerly in possession of H. Buxton Forman, is now in the Macauley Collection at the University of Pennsylvania. Specimens (Inf. i. 1-42 ; xxxiv. 127-39) were printed in New Quarterly Review, April 1877.]”7

It seemed simple enough. The manuscript was at the University of Pennsylvania library in the Macauley Collection and the excerpts were published in old periodicals that most likely could be found online. Crystal clear easy tasks.

I quickly found copies of the Literary Anecdotes of the Nineteenth Century, an online PDF and a copy of the 1895 edition, which I purchased. Now I’m thinking the rest will be easy.

Not.

Toynbee stated an excerpt was published in the New Quarterly Review, April. 1877. It was said to have published an excerpt from the Inferno. Reality was quite different. According to the University of Pennsylvania The New Quarterly Review was published from 1844 to 1847.8 In the Encyclopaedia [sic] Britannica (1911) it states The New Quarterly Review was published from 1952-1961. Searches for online PDF’s showed both sets of years to be accurate. Still not 1877 as per Toynbee. There was a New Quarterly Magazine published from 1873-1880 but Wade’s excerpt does not appear anywhere in it.

To further confuse me, there was The Quarterly Review, published from 1809 to 1967,9 but the April 1877 issue does not have the Wade excerpt. The Quarterly Review was referred to as The London Quarterly Review when reprinted as an American edition.10 The April, 1877 American edition does not have Wade’s excerpt.

I did finally find the excerpt in The London Quarterly Review, printed in London (not The London Quarterly Review, American edition), Vol. 48, April, 1877. It contains Inferno, Canto 3, lines 1-42, not Canto 1 as stated by Toynbee, and Canto 34, lines 127-139. Toynbee’s entry was most likely just a mistake. For the wealth of information he sourced and published, there are relatively very few errors. An impressive feat, in my opinion.

Two down, one to go. Now for the story of Wade’s unpublished manuscript.

I contacted the University of Pennsylvania library about the Wade manuscript in the Macauley Collection. It was during the COVID lock-down, so no one could go into the library to look. Very frustrating.

Being impatient, I started researching the H. Buxton Forman angle, as he was listed by Toynbee as the former owner. Forman was an antiquarian bookseller who was known at that time in the literary world because of his biographies on John Keats and Percy Shelley (this is not sourced because, weirdly, it was already in my head).

After Buxton’s death, his collection was sold at auction by The Anderson Galleries in New York.11 The auction took place April 26 - 28, 1920. The Thomas Wade manuscript was listed for sale in Lot 1130.12 It was on Wednesday Afternoon, April 28, during the Fifth Session, that Lots 981-1228 was auctioned.13 Trying to track down who bought Lot 1130, I contacted Anderson Galleries and they put me in contact with the Grolier Club. From them I found out Lot 1130 sold for $2.50. A buyer was not listed.14

Now a twist. Guess who bought a big chunk of Forman’s collection? Yes, the University of Pennsylvania. This is why UPenn was listed in Toynbee’s 1921 publication as having the Wade manuscript. I am very excited at this point; I just have to wait for COVID restrictions to relax so someone can get to the manuscript.

On June 8, 2020, John Pollack, Curator in Research Services, sent me an email, “We have located the manuscript in our uncatalogued collections. Of course, we cannot access it at present … we can hopefully catalog it and evaluate it for scanning … all of that may take several months.” I paid for the scans, it wasn’t cheap, but I didn’t care. I was ecstatic! Now, it was a waiting game.

A few months later, on September 25, 2020, Mitch Fraas, Senior Curator for Special Collections, sent me an email containing the PDF scans I ordered of the Thomas Wade manuscript. The lost had been found! I felt like Indiana Jones!

But when I began to transcribe the translation, I discovered the translation was not by Thomas Wade, but by Robert Watson Wade and was dated 1804. I contacted Mr. Fraas about this and he was as surprised as I! He said he would try to figure out what was going on.

On October 5, 2020, Mr. Fraas emailed me back and said, “I actually managed to get into the building today and look at our accession books. You were right. Ours is not the MS. sold at the Forman sale in 1920. We acquired the two vol. MS. with the rest of Francis Campbell Macauley's collection and accessioned it into the library in 1901 … I assume there was some mix-up between Thomas Wade's MS. (in Forman's possession) and Robert W. Wade's MS. in the Penn/Macauley collection and from there everything got confused. I can find no evidence that we ever owned the Thomas Wade MS.” No! Bummer! But YAY! A new translation!

1849 - John Aitken Carlyle - Inferno

In 1849 John Aitken Carlyle did the first literal prose translation of the Inferno titled Dante’s Divine Comedy: The Inferno. A Literal Prose Translation.15 It was published in London by Chapman and Hall and also in New York by Harper and Brothers. The US edition is the FIRST book I bought for my collection. I bought it online for $15.00! The one that started it all!

I was working on my Masters in English Literature (Rutgers University, Camden) and as part of my thesis I was translating a Medieval Romance, King Horn into octosyllabic couplets. I often got stuck staying within these limitations, so when that happened I would switch to the Inferno and translate it into terza rima. I discovered switching between the two created an inspirational cycle that would re-invigorate my creativity.

I chose the Inferno because I was teaching high school English (seniors) at the time and my students were into playing the video game called Dante’s Inferno, so I did a mini-lesson on the poem. We had John Ciardi’s translation. It was not in terza rima, so I just got it in my head to translate the Inferno into terza rima when I took a break from King Horn because I felt it would help hone my word skill for Horn, and besides, it would be fun. I have to add here that translate is not really the right word for what I was doing. Let me explain.

I was ‘translating’ King Horn from English to English. Horn is written in Early Middle English, and though it is very, very different from modern English, it still, at times, felt like I was paraphrasing the EME into modern English, but I was legitimately translating. I need to be honest, I was not translating Dante from the Italian, I started paraphrasing the English translation, Cialdi’s, into terza rima and quickly realized I did not want to capture his poetic voice in my terza rima interpretation, so I found a PDF of Carlyle’s literal prose translation and used that. The reason was that since the EME felt like paraphrasing, though I would argue it is definitely translating, the paraphrasing of a literal prose translation of the Inferno into terza rima was giving me the practice I needed to successfully complete Horn. FYI, I stopped ‘paralating’ (my word for a paraphrased translation) the Inferno after Canto 6. It was a hassle navigating the PDF on the computer, so I eventually bought the book. Then another, then another…

This Carlyle translation was used by J. M. Dent in his Temple Classics issue of the Divine Comedy released between 1899 and 1901. Philip Henry Wicksteed’s Paradiso was published in 1899, the reprint of Carlyle’s Inferno in 1900, and Thomas Okey’s Purgatorio followed in 1901.

Dayman, John. The Inferno of Dante Alighieri, translated in the terza rima of the original, with notes and appendix. London. William Edward Painter, 1843.

Dayman, John. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. London, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1865, p. viii.

Ibid, p. ix.

Wade, Robert Watson. The Inferno of Dante. Translated from the Original. In Blank Verse. Together with the Life of the Author. Unpublished, London. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Macauey Collection, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. UPenn MS Codex 2045, 1804.

Toynbee, Paget. Dante in English Literature, in Two Volumes, Vol. 2. London, Methuen & Co., 1909, p. 627.

Ibid.

Toynbee, Paget. Britain’s Tribute to Dante, London, Oxford University Press, 1921, p. 100.

“The Online Books Page.” The New Quarterly Review Archives, University of Pennsylvania library. onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/serial?id=newqtlyrev1844. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

“Quarterly Review.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quarterly_Review. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Wikipedia sourced this information from:

Jonathan Cutmore (ed.), Conservatism and the Quarterly Review: A Critical Analysis (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2007).

“Quarterly Review.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quarterly_Review. Accessed 31 Aug. 2024.

Wikipedia sourced this information from:

Jonathan Cutmore, Contributors to the Quarterly Review 1809-25: A History (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008).

The Library of the late H. Buxton Forman. The Anderson Galleries, 1920.

(The book is broken up into three parts within one volume. Each part has its own series of numbers beginning with page 1.)

Ibid, [Part Two] p. 162.

Ibid, [Part Two] p. 3.

"Founded in 1884, the Grolier Club is America’s oldest and largest society for bibliophiles and enthusiasts in the graphic arts.” from grolierclub.org. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Carlyle, John Aitken. Dante’s Divine Comedy: The Inferno. A Literal Prose Translation, with the text of the original collated from the best editions, and explanatory notes. New York, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1849.