Here are the remaining 18th century excerpts. One is a ‘found’ translation in which a bit of help would be appreciated.

I just want to note that there were quite a few translators of excerpts not included in this list. I felt they were not “sustained” enough. They were typically 6 lines or less, usually less. For a complete list of all those little translations see Paget Toynbee’s Chronological list of English translations from Dante from Chaucer to the present day (1380-1906).1

1782 - Charles Burney

I have already discussed Burney in my first post, The First Translations: Unpublished. His published translation excerpts are not really that long, 19 lines and 11 lines, but I mention him here again because he did translate the Inferno, though it was never published. His excerpt is in his History of Music.2 He translated a passage from the Purgatorio, Canto 2, lines 73-92 and 106-117, written in heroic couplets.

1785 - William Parsons

William Parsons broke with the 18th century ‘tradition’ of translating the Ugolino episode. Instead, he translated an excerpt from Canto 5 of the Inferno known as the Paolo and Francesca episode. His translation coincided with Dante’s lines 25 -142 and is in heroic couplets. Though there were 2 complete translations of the Inferno by 1785, Parsons was the first to translate the Paolo and Francesca episode as a separate piece and it appears in the book The Florence Miscellany. His translation inspired quite a few future translators to also choose this episode.

c. 1785 - William Parsons (again)

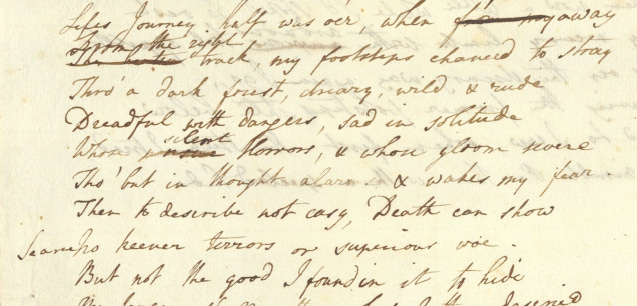

Here is another ‘found’ translation.3 It is not mentioned in any of the primary sources listing English translations of Dante.4 It is an unpublished manuscript of the Inferno, Canto 1, lines 1-33, in heroic couplets. The manuscript is part of the Bertie Greatheed Papers in the Yale Library.5 The exact year of this translation is not known.

Here is a transcription of all 33 lines:

Life’s journey half was o’er, when from my far awayThe beaten From the right track, my footsteps chanced to stray

Thro’ a dark forest, dreary, wild & rude [Through]

Dreadful with dangers, sad in solitude

Whose ??? silent horrors, & whose gloom twere [‘twere]

Tho’ but in thought alarm & wakes my fear. [Though]

Then to describe not easy, Death can show

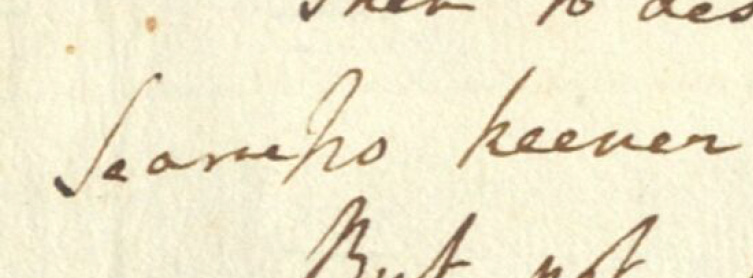

??? No keener terrors or superior woe. (can’t make first the word out)

But not the good I found in it to hide

My tongue shall utter what I there denied

Tho how I thither came, or left my way [Though]

With slumber much oppressed I scarce can say.

Soon as I reached a mountains rugged baseAnd That marked the limits of this fearful place

Upwards I gazed, & viewed its airy head.

Bright with the fiery planets glowing red.

That friendly orb whose lustre so refined,

In all pursuits the guide of all mankind

Then fled my fear, & all my grief was oer, [o’er]

The nights anxiety opprest no more. [oppressed]

Like the poor wretch who safe arrived

With heart quick beating, hears the tempest billows roar

And turns to view, with doubt, and looks agast [aghast]

On all the watry dangers he has past [wat’ry]

So now my mind, that shuns the danger oer [o’er]

Views the dread pass, no mortal life crossed before

When now a little while, I’d stoped to rest [stopped]

My weary limbs with ??? arduous toil opprest [oppressed]

As oer the dreary way again I go, [o’er]

Leaving the firmer footsteps still below.

And lo I saw, when first the steep I tried steep = side of mountain

A nimble panther with a speckled hide

Two things I have questions about. First, Parsons uses the word oppressed three times. The first time he spells it ‘oppressed,’ but the next two times he uses the word he spells it ‘opprest.’ Is this just an abbreviation or is there some old grammatical rule I don’t know?

Second, there is one word not crossed out that I am unsure of. It seems to be in the margin before the words ‘No keener.’ I see Scarse or Scarce. Any thoughts?

1794 - Henry Constantine Jennings

In 1798 Henry Constantine Jennings published a second edition of Summary and Free Reflections, in Which the Great Outline Only, and Principal Features, of the Following Subjects Are Impartially Traced, and Candidly Examined. In it he translates excerpts from the Inferno. Though published in 1798 the book states the translations were done in 1794. The translations are NOT in the 1783 (first) edition.

The translations are of Canto 5, the Paolo and Francesca episode, in its entirety, though Jennings translation is condensed by 35 lines, and Canto 33, the Ugolino (he spells it Hugolino) episode. He combines the end of Canto 32, lines 125 to 139, with the beginning of Canto 33, lines 1-87. Jennings said this about his combined cantos, “Taken from the end of Dante’s 32d Canto … and the greater part of the 33d … united so as to form one consistent Ensemble.”6

The next post will return to the chronological order of translations which will cover the early 19th century Infernos (1805-1812) by Cary, Howard, and Hume.

Toynbee. Paget. “Chronological list of English translations from Dante from Chaucer to the present day (1380-1906).” Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the Dante Society, 1905. Boston, Ginn & Company, 1906.

Burney, Charles. History of Music. Vol. 2, London, Printed for the Author, 1782.

(The excerpt is on pages 322 and 323.)

These primary sources are by Paget Toynbee and Gilbert Cunningham. Their bibliographies can be found at the bottom of my About page under Resources.

Bertie Greatheed Papers. “Series II: Manuscripts, 1766-1813.” James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Call Number: OSB MSS 68, Series II, Box 2, Folder 52.

Jennings, Henry Constantine. Summary and Free Reflections, in Which the Great Outline Only, and Principal Features, of the Following Subjects Are Impartially Traced, and Candidly Examined. Privately printed, 1798.

(NOTE - Page numbers repeat. The translations are on the 8th instance of pages 7 through 18.)