Between 1860 and 1869 there were five stand alone translations of the Inferno and five translations of the Divine Comedy, four were completed within this decade, along with the last 2 volumes of John Wesley Thomas’ Comedy (his Inferno was published in 1859).

This post will cover translations of a cantica or more. In two previous posts, Partial Translations: 1782-1849, Part 1 and Part 2, I discussed the dozen partial translations of at least one canto. A future post will pick up with 1850 and continue to discuss these incomplete translations.

The translators in this batch include the first woman to publish a translation of a cantica or more, Claudia Hamilton Ramsay, as well as the first American to do the same, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. By the turn of the nineteenth century Longfellow’s translation was replacing Cary’s as the most popular go-to version. He will only be briefly mentioned here because he will get his own post.

Here is the list:

1862 - Hugh Bent [George Atty] - Inferno

1862 - Claudia Hamilton Ramsay - Inferno, vol. 1

1862 - Claudia Hamilton Ramsay - Purgatorio, vol. 2

1862 - John Wesley Thomas - Purgatorio, vol. 2*

1862 - William Patrick Wilkie - Inferno*

1863 - Claudia Hamilton Ramsay - Paradiso, vol. 3

1865 - John Dayman - Divine Comedy (published Inferno in 1843)

1865 - James Ford - Inferno (published the Divine Comedy in 1870)

1865 - William Michael Rosetti - Inferno *

1866 - John Wesley Thomas - Paradiso, vol. 3

1867 - David Johnston - Inferno, vol. 1

1867 - David Johnston - Purgatorio, vol. 2*

1867 - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow - Divine Comedy*

1867 - Thomas William Parsons - Inferno

1868 - David Johnston - Paradiso, vol. 3

Translations in my collection are marked with an asterisk. All pictures are from my collection (unless noted). All titles are linked to PDF’s where available. This list does not include partial translations of which there were many.

1862 - Hugh Bent [George Atty]

In 1862 Hugh Bent translated the Inferno.1 For well over a decade I have been looking for an extant copy, yet it has eluded me, until now. Since 1862 Bent’s translation has been in all the 19th century translator lists under the title Inferno. These lists also state that it was privately printed and that Hugh Bent is a non de plume, a pseudonym. Further, all the contemporary sources claim there are no extant copies. I believed this for over well over a decade. I searched on line, used WorldCat, contacted numerous libraries, and in frustration would give up only to start again a few years later. Nothing. While writing this post, I again decided to give it a go.

It turned out differently.

All searches (like usual) were coming up empty, so I pivoted to anything else he might have written with the hope it would give me a clue. There was a Hugh Bent in WorldCat for Torquato Tasso, his Jerusalem Delivered, Englished in Octaves, a two volume translation published in London by Bell & Daldy in 1856. I already knew about this. It exists in four libraries (according to WorldCat). I used Torquato Tasso to dig further and eventually got a hit on a site called “Wellcome Collection.” This sounds like I typed it in and got the hit, but that is not what happened. In reality it wasn’t until well over an hour, cussing at my computer, giving up twice, then coming back, and cussing a whole lot more before I got the hit AND this was the only hit. Imagine Googling something and getting only one hit! I don’t even remember what I specifically typed in the search bar. On the site there was a link that gave me this hot mess:

Yeah, it’s near impossible to see. This was just a big black scrolling block of tiny words. I searched key word for Bent and got a hit. It was his Jerusalem Delivered, but in brackets it gave the name George Atty. Brackets are typically used to indicate an author’s real name after a pen name. I felt Indiana Jones whispering in my ear, “This could be the key!”

And it was! I tried “George Atty” using quotes in WorldCat and… POOF! There it was, right in front of me, so simple, and it was in two libraries. Now, I was really mad that I have wasted so much time over the years looking for this book and needed to know why it was so hard to find, why for over ten years it eluded me.

This is what I figured out. WorldCat has the title listed as The vision, first part: or, Hell of Dante Alighieri. The issue was that every source gave its title as Inferno, so if you search for Inferno as the title and narrowing the search to just 1862 (which I originally did), it will not appear because Inferno is not in the title. OK, honest mistake, can’t believe I never tried “Hell” and narrowing the year to 1862. I feel stupid. Lesson learned.

But wait, there’s more. There is a glitch that definitely contributed to this title being so hard to find (i.e. hidden). The listing has Hugh Bent listed as the author/translator, but doing an author search using “Hugh Bent” only brought up Jerusalem Delivered. When searching using the author, the book only appeared when I typed in “George Atty,” yet (again) the listing clearly has Hugh Bent listed with Dante as the authors. Explain that. In any case, I am stoked that I found it. Now, if I can only find the actual book for my collection.

There is no PDF online, so I am working on getting a scan of the whole book from one of the two libraries that has a copy. I did get a PDF scan of the title page from Cambridge:

1862-1863 - Claudia Hamilton Ramsay

In 1862 Claudia Hamilton Ramsey published the first two volumes of the Divine Comedy, the Inferno and Purgatorio,2 and followed them in 1863 with the third volume, Paradiso.3 They have really long titles with the last word of the title naming the specific cantica, Dante’s Divine Commedia. Translated Into English, in the Metre and Triple Rhyme of the Original with Notes. Inferno (or Purgatorio, or Paradiso).

With her publication of the Inferno, Ramsey became the first woman to publish a full cantica. After the release of her Paradiso, she became the first woman to publish the Divine Comedy. Also, her translation is in terza rima and, you guessed it, she was the first woman to do so. It will be 42 years before we see another cantica translated by a woman.

Her full name is missing from the title page of all three volumes. Instead it just says, “Mrs. Ramsey.” It is interesting to see the reviews of her translation. Reading between the lines you can hear the societal misogynistic attitude towards women who dared to enter the realm of scholarship traditionally ruled by men.

A good example is in The Saturday Review (1863), “while her style of translation is distinguished by much fidelity and a remarkable degree of elegance … [t]hat she should often fall very short of the nervousness and precision of the masculine style with which she has to cope could not but have been expected.”4 According to this reviewer it was expected that she couldn’t cope with Dante’s “masculine style.” Masculine style? What? This reads like a polite version of “How dare she! This is man territory!” An anachronistic idea, like Lady Macbeth who dared to take on the role of a man, that this is not her place. Seems to me a begrudging compliment with thinly veiled reminders of her gender’s shortcomings. Am I reading too much into this? Let me know in the comments below.

I definitely plan to explore women translators as a whole in a future post.

I have never seen a copy of this for sale. Ever.

1859-1866 - John Wesley Thomas

Between 1859 and 1866 John Wesley Thomas published the Divine Comedy. The Inferno was published in the previous decade, 1859. In this decade he published both Purgatorio and Paradiso. The Trilogy; or Dante’s Three Visions. Part II. Purgatorio5 in 1862, and in 1866, The Trilogy; or Dante’s Three Visions. Part III. Paradiso.6 Like his Inferno, these are in terza rima.

Thomas was already discussed in the previous post, Dante Translations: 1850-1859, so go there for the details.

I am only missing his 1866 Paradiso. An incomplete set drives me crazy!

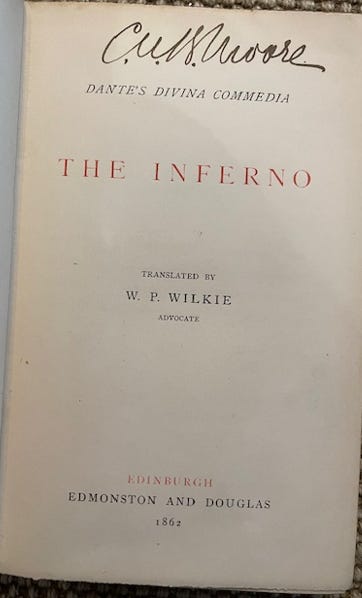

1862 - William Patrick Wilkie

In 1862 William Patrick Wilkie published Dante’s Divina Commedia. The Inferno.7 His translation is kind of in blank terzine.8 I say “kind of” because the lines are of irregular length. Maybe I should call it free verse terzine, but free verse poetry didn’t exist in 1862 (you can thank Walt Whitman for that travesty) and terzine is a form and free verse implies no form, so blank terzine with irregular lines it is.

One scholars call this “merely a curiosity” as the “renderings of some lines are so entirely unconnected with the Italian that one certainly could not hold any editor responsible for them”9 and “the work itself is almost completely valueless.”10 Ouch!

A revised edition was published in 1866, but only the first eight cantos were revised, the rest remains identical to the original.

1865 - John Dayman

John Dayman already released his Inferno in 1843, previously discussed in Dante Translations: 1840-1849. In 1865 he published The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri,11 also in terza rima.

Commenting on his choice of terza rima for the translation in the expanded preface of the 1865 Comedy, Dayman says his previously published Inferno was “denounced as the one ‘deleterious ingredient’ which corrupted the version throughout.”12 He refutes this with a quote from Augustus William Schlegel’s book, Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, “It [the translation] must act according to laws derivable from its own essence, otherwise its strength will be evaporated.”13 I take it he feels that the structure is key to the strength of the poem and I agree, though not always successful in translation.

I have the 1843 Inferno, but not this. Yet.

1865 - James Ford

James Ford published his Inferno in 1865, The Inferno of Dante. Translated in the Metre of the Original.14 Like Dayman and his other contemporaries, his translation is in terza rima. Later, in 1870, he published the complete Divine Comedy.

Like previous translators, he feels he has to justify his choice of terza rima. He says using terza rima presents “great difficulties and risk of failure” and further adds, “it is not surprising that it should have been less adopted by our different translators.”15 Speaking of blank verse he says, “Blank verse at once rids us of these difficulties [terza rima]; but then, in its tendency to diffuseness, it seems ill fitted to represent a metre … so succinct.” Ford believes by changing the form of Dante’s original it loses its strength, something important. By succinct I believe he is referring to “the clause, if not the sentence, generally closes with the triplet, and so confines the sense.”16

I have the 1870 Comedy (which will be covered in the next decade), but can’t find the 1865 Inferno, so I am not sure if he made revisions with the new release.

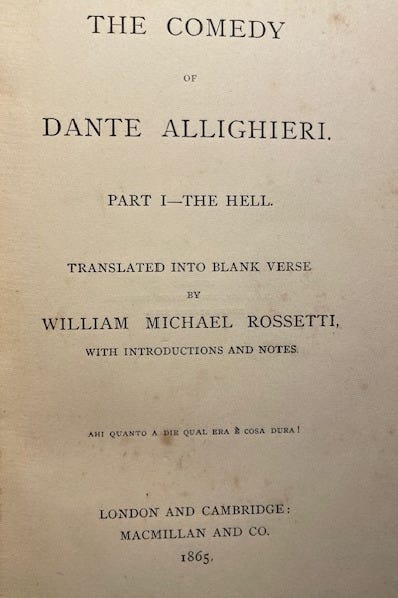

1865 William Michael Rossetti

William Michael Rossetti published his Inferno in 1865, The Comedy of Dante Allighieri [sic]. Part I - The Hell.17 It was translated into blank terzine (see footnote 8). I find it interesting he calls this Part I. To me that implies that there will be a Part II, especially since he was dealing with a three-part poem. Unfortunately, none was forthcoming. Further, it is interesting that he spelled Dante’s last name Allighieri, not Alighieri. I wonder if it was on purpose?

If Rossetti’s name sounds familiar that is because he is part of the famous Rossetti clan which includes Dante Gabriel (artist and poet), Maria Francesca (Shadow of Dante, 1871), and Christina Georgina (poet). His older brother, Dante Gabriel, is without a doubt the most famous of the group. He was a famous painter and poet. Further, he is known for translating Dante’s La Vita Nuova (The New Life) and the Ugolino episode from Inferno, Canto 33.

This was a hard find and I am lucky to have one.

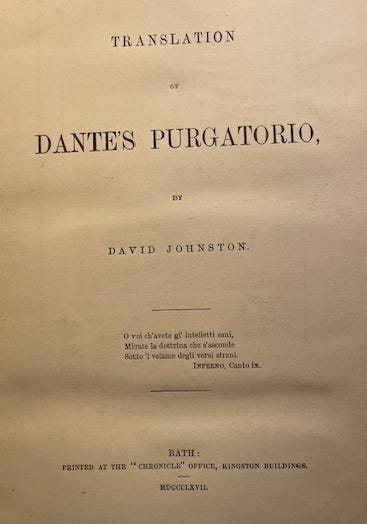

1867-1868 David Johnston

Over a two year period 1868 David Johnston published his Divine Comedy in three volumes. The Inferno18 and Purgatorio19 in 1867, and Paradiso20 in 1868. All are titled similarly, A Translation of Dante’s [insert cantica]. His translation is in blank terzine (see footnote 8).

Johnston had his Divine Comedy privately printed “to promote the study of Dante among his friends … and printed it in three handsome volumes as a present, to encourage this laudable pursuit.”21 How cool. His motivation was making sure his friends could experience Dante.

I did acquire Purgatorio which, interestingly, is dedicated to James Ford. Yes, the guy mentioned above who published his Inferno in 1865 (and the Divine Comedy in 1870).

Privately printed editions are rare and very hard to find. I have Purgatorio (pictured), but the other two elude me.

1867 - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

In 1867 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his Divine Comedy. This translation like Cary’s, was reprinted often and by the early 20th century replaced Cary’s as the go to translation.

Longfellow was the next big important translation after Cary and because of this I will discuss him further in his own post.

1867 - Thomas William Parsons

Thomas William Parsons began publishing translated excerpts from the Inferno in 1843 when he published The First Ten Cantos of the Inferno of Dante Alighieri. Newly Translated into English Verse. This was followed in 1865 with the addition of seven more cantos, Seventeen Cantos of the Inferno of Dante Alighieri. It was in 1867 that he finally published his complete Inferno22 titled The First Canticle, Inferno, of the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. It was written in heroic quatrains.23

He followed this with the first nine Cantos of Purgatorio under the title Ante-Purgatorio of Dante Alighieri in 1875 (1876 in Britain), and in 1893, a year after his death, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri was published, a complete collection of his Dante translations. It contain the Inferno (1867), a bit more than half the Purgatorio, and a few partial excerpts from Paradiso.

My collection only contains the 1843, and the 1865 partial translations of the Inferno, as well as the 1893 complete collection of his works. When I get to the 1890’s I will do a deep dive on Parsons.

I should have split this in two posts as I truncated a few of the sections to save time. I’ll know better next time.

Thank you for reading.

Bent, Hugh [George Atty]. The Vision, First Part: or, Hell of Dante Alighieri. Privately printed, London, R. Clay, Son, and Taylor, 1862.

Ramsey, Claudia Hamilton. Dante’s Divine Commedia. Translated Into English, in the Metre and Triple Rhyme of the Original with Notes. Inferno. London, Tinsley Brothers, 1862.

Ramsey, Claudia Hamilton. Dante’s Divine Commedia. Translated Into English, in the Metre and Triple Rhyme of the Original with Notes. Purgatorio, London, Tinsley Brothers, 1862.

Ramsey, Claudia Hamilton.Dante’s Divine Commedia. Translated Into English, in the Metre and Triple Rhyme of the Original with Notes. Paradiso. London, Tinsley Brothers, 1863.

“Mrs. Ramsey’s Dante.” The Saturday Review. No. 420, Vol. 16, Nov. 14, 1863, p. 653.

Thomas, John Wesley The Trilogy; or Dante’s Three Visions. Part II. Purgatorio, or the Vision of Hell: Translated into English, in the Metre and Triple Rhyme of the Original; With Notes and Illustrations. London, Henry G. Bohn, 1862.

Thomas, John Wesley. The Trilogy; or Dante’s Three Visions. Part III. Paradiso, or the Vision of Hell: Translated into English, in the Metre and Triple Rhyme of the Original; With Notes and Illustrations. London, Henry G. Bohn, 1866.

Wilkie, William Patrick. Dante’s Divina Commedia. Edinburgh, Edmonton and Douglas, 1862.

Blank terzine is blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) divided into three line sections that coincide with Dante’s terzine. The term was first coined (as far as I could find) by Gilbert Cunningham in his 1954 doctoral dissertation The Divine Comedy in English, A Critical Bibliography, 1782-1954.

Cunningham, Gilbert F. The Divine Comedy in English, A Critical Bibliography, 1782-1900. Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd, 1965, p. 89

Ibid, p. 92.

Dayman, John. The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. Translated in Terza Rima. London, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1865.

Ibid, p. viii.

Ibid.

Ford, James. The Inferno of Dante. Translated in the Metre of the Original. London, Smith, Elder, and Co., 1865.

Ibid, p. xii.

Ibid.

Rosetti, William Michael. The Comedy of Dante Allighieri [sic]. Part I - The Hell. Translated into Blank Verse. London and Cambridge, Macmillan and Co., 1865.

Johnston, David. A Translation of Dante’s Inferno. Bath, Printed at the “Chronicle” Office, 1867.

Johnston, David. A Translation of Dante’s Purgatorio. Bath, Printed at the “Chronicle” Office, 1867.

Johnston, David. Translation of Dante’s Paradiso. Bath, Printed at the “Chronicle” Office, 1868.

“A Translation of Dante's Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. By David Johnston. 3 vols.” Athenaeum. No. 2176, July 10, 1869, p. 48.

Parsons, Thomas William. The First Canticle, Inferno, of the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. Boston, De Vries, Iberra and Company, 1867.

A heroic quatrain is a stanza of four lines in iambic pentameter with either an alternating rhyme scheme (ABAB) or rhymes in couplets (AABB) . Also known as an elegiac quatrain.

Great post!